Effective Efficient Kubernetes Debugging

Context test debugging

David Wu & Carlos Nunez

In the previous learning path on a heuristic approach to debugging, you learned about the top six common sources of problems. You also learned how to use these top six sources as heuristics that help pinpoint the issue when there are too many possibilities, or when you don’t have enough information to know where to begin. One practical aspect of the heuristics approach is how it limits the scope of a problem space, but it can fail to account for other factors in a system at the same time. For example, NTP. Is there a way to avoid this? Yes, this learning path presents a concept and technique on how to do this.

What You Will Learn

In this section, you will learn:

- Context test debugging.

- The Dump In, Sink Out method for group based problem solving.

Refined Heuristics with Context Test Debugging

The most important aspect to consider is, “Where do you look in a large system?”. We describe this as the context. It is possible to infer and search for all areas previously described without context. However, sustainable debugging of systems is best served with a good understanding of how a system works, followed by debugging practices to become proficient and efficient. Understanding how a system works means you know how the ’engines’ run.

For example, What are the components involved? True understanding is not simply being able to describe it in plain words, but also being able to draw it. Can you draw out the system and data flows? Yes, even if the diagram is simple, draw it because this reduces cognitive load while thinking of the issue at hand for large complex problems. Some typical diagramming tools can assist, including Miro, LucidChart and, draw.io.

One way to start is top-down. Understand the bigger picture, then dive into the individual components. On much larger systems, focus on areas of the architecture that is relevant to the scope of the problem. It is OK to not understand everything at once. More importantly, is the mindset of determination and curiosity of wanting to know it with an open mind. Once a picture of the system is available, the focus would be on identifying what parts of the system are in context to the problem. For example, components that are closely related/connected to where the issue is first seen. Once the context of the system is identified, you can start hypothesizing and prioritizing what issues and tests to perform. It is not necessary to hypothesize within the context of the system, but it does help to limit the amount of hypotheses and tests that need to be performed to areas that are likely the source of an issue.

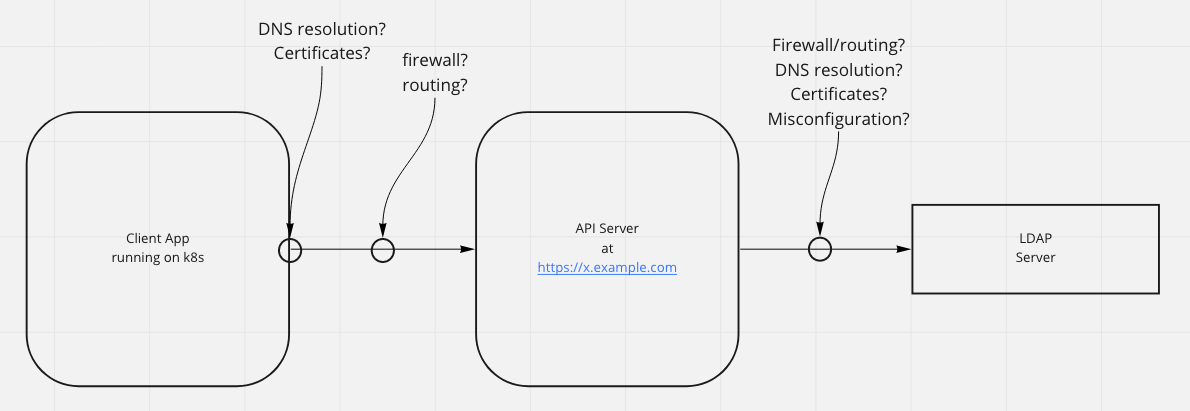

In the following diagram, you can see that there are number of places where an issue can occur. Having a diagram with its data flows on hand allows hypotheses and prioritization of issues, and lets you perform tests at each point to see if the hypothesis holds. It is here that the sources of problems described in the previous learning path, can be assigned as a hypothesis. Having this picture, you can prioritize where to perform tests. The tests usually start with components that are closely related to where the issue first originated. Always start small, and expand the scope as needed.

Group Based Brainstorming - Dump In, Sink Out

The previous section looked at forming contexts of a system and hypothesizing where issues may originate. For resolving most problems, a single person or a pair of people is sufficient. However, for larger scale, complex and unknown systems, a team of people are best utilized for identifying and solving complex problems. This is because experience and different knowledge/perspectives to a problem can be gathered and used to form additional hypotheses to tests. However, how does one effectively conduct this? The key is to use brainstorming techniques, such as the ones discussed here.

This section introduces the Dump In, Sink Out (DISO) approach that was utilized and devised by S. Wittenkamp and D. Wu for the context of solving a problem in a very large complex software system with a team of developers. This idea is furthered in this article by incorporating the concept of the context system diagram.

The following are the basic requirements for all participants:

-

A basic knowledge of the problem. For example, all participants knows Kubernetes.

-

A good understanding of the system, a system expert, or an expert who can interact with internal or external components.

-

Access to the system, preferably in pairs.

If done in person, materials should include sticky notes, painter tape and markers. The assumption is that you are the facilitator. You may assign this to someone else to conduct.

To conduct DISO, do the following:

- Setup: Before starting the session, set up a whiteboard.

- Introductions: Provide a brief description about the scope of the system, the problem encountered, and any additional debug information. Define the goal of the exercise, then show a drawing of the system and explain what it represents.

- Hypothesize: This is the dump in phase. Provide sticky notes and markers

to the participants. Ask them to write each idea on a

sticky note, then place them on the diagram of the system, in the

Hypothesesarea of where the problem might exist. Have the participants do this alone to avoid biases, and within a limited time. For example, 10 minutes. Encourage the participants to write down their ideas, reminding them that there are no ‘bad ideas’, and that it’s OK if ideas are duplicated independent of other participants.

- Grouping: The facilitator reads each sticky note aloud, then asks the

participant who wrote it to explain the idea and the reason. The facilitator

then moves the sticky note to the

Grouping and Priorityarea. Group ideas that overlap together.

- Prioritization: The facilitator prioritizes the sticky notes (or groups of sticky notes) by moving those that have a greater likelihood of cause to the problem to the top, and those that are not likely to the bottom.

- Testing: This is the sink out phase. Each participant, grouped in

pairs, tests each hypothesis for the prioritize groups of sticky notes at the top of

the list. Once each hypothesis is tested, the pair moves the sticky note and the results

to the

Testedarea. The pair must also document their testing methodology.

Eventually, the test results should provide an answer as to where, or what is the cause of the problem. If the test results does not provide an answer, consider the other interacting components or systems. If there is a bug, reach out to support. For example, IaaS providers and support is required from them if they are not part of the current group of participants.